Book Review: Feathers, the Evolution of a Natural Miracle

By Sheila Montalvan

Feathers, the Evolution of a Natural Miracle. By Thor Hanson. New York, NY: Basic Books. 2011, 336pp.

Recently I heard about an exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York called Dinosaurs Among Us that features a 23-foot- long feathered tyrannosaur (Yutyrannus huali) and a small dromaeosaur with “four wings and vivid plumage.”

Information on the exhibit states that, “the boundary between the animals we call birds and the animals we traditionally called dinosaurs is now practically obsolete”, and that “many dinosaur species sported primitive feathers—precursors to those birds use to fly, court mates, and more.” This information would have astounded me, except that I happened to be reading Thor Hanson’s well-informed book, Feathers. Dr. Hanson, a biologist and author, won the American Museum of Natural History John Burroughs Medal for Feathers, and was nominated for the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize in the UK.

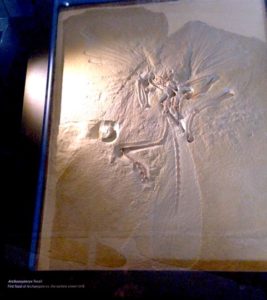

According to Dr. Hanson, it all started in the German countryside in 1861. A quarryman, who “worked in a world of dust, the fine grit of limestone powdered by blasting, chisel work, and constant hammer blows”, had a very bad cough. Unable to afford a doctor, his “method of payment was a delicate, crow-size fossil he had found that would change science forever.” The fossil was Archaeopteryx lithographica –a fossil of a reptile with the feathers of a bird.

Archaeopteryx lithographica fossil

Fossils are known to be fairly common in limestone, and sometimes miners would smuggle out any interesting finds to trade for necessities, such as medical advice. The doctor knew he had something special, and the fossil eventually ended up in London where its origins and meaning were debated by scientists for years. The fossil is now in the Natural History Museum in London. I was fortunate enough to see the actual fossil while in London recently. It is kept in the “Treasures” section of the museum and is their “most valuable fossil” (see photo). It is larger than I thought it would be, and even to my untrained eye I could tell it was a bird by the shape and feather detail. Seeing the fossil certainly put the author’s enthusiasm on the subject into perspective.

The book touches on a wide variety of feather trivia. Did you know that early humans probably used feathers to create paintings in caves? Or that the metallic fins on the “massive rocket that launched Apollo 15 were direct technological descendants of the first feathers to stabilize the tail end of a dart”? And that the “word pen is derived from the Latin penna, for feather.” Feathers were also used for dental hygiene purposes, back in the day.

The author informs us that there is a desert dwelling bird called the sandgrouse, who will fly to a water source and carry water back to its young in its breast feathers. The water source can often be 30 miles away. Sandgrouse feathers actually absorb the water – and “will hold two to four times as much water as the average dish sponge.” The sandgrouse chicks are able to get a sip of water since they are unable to fly to the water source yet.

Another section examines how feathers get their pigment, and how scientists determined that feathered dinosaurs were colorful. Did you know that the coloring in parrot feathers makes them resistant to bacteria? Perfect for life in a damp rain forest.

There is plenty of discussion on feather anatomy, too. The author provides a very detailed visual reference to various types of feathers, including their size and structure. Everything one needs to know (and more) about flight and contour feathers, bristles, follicles, filaments and filo plumes are here.

This insightful, easy to read book is consistent with Dr. Hanson’s engaging style and enthusiasm for the subject. Feathers contains a variety of biological, cultural, scientific, and religious information that would appeal to most readers. Any naturalist or bird watcher would benefit from reading this book, and you won’t want to miss a single part.

Link to Publisher’s page: http://www.basicbooks.com/full-details?isbn=9780465028788